Pressemitteilung: Über Roger Enos neues Album “The Turning Year” – 22.4.2022 (VÖ) (English only)

14.01.2022

English only

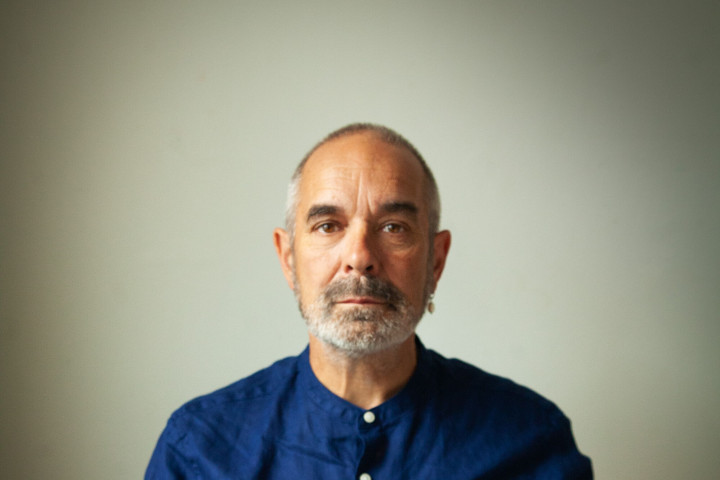

Roger Eno: The Turning Year

Roger Eno grew up in the idyllic setting of Woodbridge, Suffolk, with an East Anglian postman father and a Flemish mother, who gave him and his younger sister “one room of the house, which was devoted to whatever we children wanted to do. We could write on the walls, there was a sandpit, there was a busted-up piano we could knock seven bells out of. The town had a lovely river, so there was swimming, great places to cycle, and it was perfectly acceptable for a child to leave in the morning and not turn up till tea time.” It’s therefore little surprise he continues to live in the same locale, spending his spare time wandering the countryside on foot or by bike. “What keeps me in a not entirely enlightened country is my continuing love of the area in which I live.”

Along with its bucolic, tranquil qualities, a timeless character is key to the magic of Roger’s music. That’s as true of 1983’s Apollo: Atmospheres And Soundtracks – which, composed with his brother, Brian Eno, and producer Daniel Lanois, launched his recording career – as it is of The Turning Year, his debut solo album for Deutsche Grammophon, due on 22 April 2022. Recorded during the summer of 2021, largely at Berlin’s legendary Teldex Studio and in part at the studio of producer Christian Badzura (also the label’s Director of New Repertoire), it’s an album of grace, purity, melancholy and solace which showcases his free-flowing inspiration and deeply affecting compositions. It’s also given him a chance to remind us of his talents as an arranger, with its compelling piano melodies elevated on some tracks by Scoring Berlin’s 20-piece string ensemble, and by clarinettist Tibor Reman, who adds enchantment to the elegiac “On the Horizon”.

From the hypnotic calm of the opening “A Place We Once Walked” to the closing “Low Cloud, Dark Skies”, whose rippling arpeggios are lent gravity by the string section’s sustained chords, The Turning Year uses so-called classical orchestration, so it’s rooted in a tradition. But it’s a tradition that’s taken further rather than abandoned – for example a great deal of thought was put into the running order of the recording, allowing each piece to become a short story in a volume. These “stories” were compiled from pieces written both very recently and longer ago, and manifest themselves in the likes of “Slow Motion”, a piece for strings whose unhurried pace provides a gentle passage towards the devotional “Hymn”, and “An Intimate Distance”, whose solitary piano projects a quiet sense of yearning. The frugal simplicity, too, of the emotionally eloquent “Clearly” and intimate “Bells” is counterbalanced by the slow-burning elegance of “Hope”, whose ghostly silences are met with moments of unblushing, touching sentimentality, while the understated optimism of “On the Horizon” evokes the still minutes after a storm. The brittle beauty of “Something Made Out Of Nothing”, meanwhile, refers to the way in which “‘a thing’ can be made of all but nothing, like the movement of reeds caused by the weakest of breezes”, but its title could also encapsulate Roger’s improvisational techniques, illuminating The Turning Year’s singular mix of formality and informality. “I’m not a fan of ‘the precious’,” he agrees, “and don’t like the idea of exclusive clubs.”

This is evident in how this composer has always worked. Roger went to Colchester Institute at the age of 16 to study music. His public career began after he was inspired by the pioneering proto-minimalist composer Erik Satie to stretch his methodology to its logical conclusion. “I came up with this 90-minute tape where virtually nothing happened whatsoever,” he recalls, and on its strengths his brother invited Roger to join him and Lanois in Canada to record Apollo…, the highly acclaimed score to For All Mankind, Al Reinert’s documentary about the Apollo moon landings. Two years later, EG Records released Roger’s first solo album, Voices, a piano record which nonetheless owed a similar debt to both Satie’s influence and Brian’s production, while 1988’s Between Tides saw him step away from such electronic embellishments and draw on both his love for Baroque music and his arranging skills to write something more akin to chamber music.

For 1992’s The Familiar, Roger teamed up with Kate St. John – then best known for her work with The Dream Academy – to mix pop, classical, ambient, folk, minimalism and more for a vocal record which defied genres, and on 1994’s Lost In Translation and 1996’s Swimming he expanded his horizons further, singing for the first time and adding new instruments to his armoury. (The latter, for example, opens with “The Paddington Frisk”, performed on accordion and named after an 18th-century term for the disquieting dance of the hanged.) Over the next two decades, more solo albums followed, most recently 2018’s Dust of Stars, which, produced by Youth, returned him to the style of Voices.

Amid all this, he scored Trevor Nunn’s acclaimed 1998 production of Harold Pinter’s Betrayal at London’s National Theatre, and recently finished work on his second series of Nick Hornby’s celebrated State of the Union, directed by Stephen Frears. He and his brother also continued collaborating on film music, contributing to David Lynch’s Dune (1984), Adrian Lyne’s 9½ Weeks (1986), Dario Argento’s Opera (1987) and Danny Boyle’s Trainspotting (1996), while their score for Boyle’s BBC mini-series Mr. Wroe’s Virgins (1993) was nominated for a BAFTA. In addition, Roger’s joined the likes of Lol Hammond, Peter Hammill, No-Man (co-founded by Steven Wilson) and Italian ensemble Harmonia, as well as his first “band”, Channel Light Vessel, formed with Laraaji, Bill Nelson, Kate St. John and Japanese cellist Mayumi Tachibana. He’s also teamed up as a session musician and band member with artists as diverse as The Orb, Lou Reed, Jarvis Cocker and Beck, and that’s not to mention his three-year stint as musical director for Tim Robbins and the Rogues Gallery Band. Furthermore, he’s hosted events as an accompanist, performing improvised music to well-known, early 20th-century silent films and archive home footage, obtained and licensed from the British Film Institute, and he’s a member, too, of the Church of Spiritual Humanism, which recognises humanity’s need for rites and rituals, even among those of a non-orthodox leaning, and for whom he’s officiated over multiple “non-religious but sensitive services”.

The Turning Year follows 2020’s Mixing Colours, his first full-length album recorded exclusively with his brother and compiled from pieces Roger had shared for over 15 years with Brian, who worked on them further with his own renowned digital enhancements. It was released in the same month that the Covid pandemic forced global lockdowns, when it swiftly became a staple of people’s newly muffled lives.

Listening to Roger’s impressive discography, it’s clear he’s always been prescient, and one year after Mixing Colours, he and Brian joined one another for the first time on stage, bolstered by Roger’s daughter Cecily and Brian’s regular collaborators Leo Abrahams and Peter Chilvers. In the extraordinary surroundings of the Acropolis in Athens, they performed material new and old from across their mutual catalogues, and the packed, enthralled crowd was yet another sign that the world is at last catching up with their innovative, inventive aesthetic. Now, with The Turning Year, there’s no escaping the fact that, though he’s never sought it, Roger Eno is in the spotlight.

Mehr von Roger Eno